Have you ever wondered: Are humans naturally plant-based eaters? Is our body truly meant to eat meat, or are we actually designed for a plant-based diet? The debate between meat-eaters and vegetarians often gets heated, but today, let’s take a calm, science-based look at this question. Explore the fascinating truth behind human anatomy, digestion, and evolution — and discover why our bodies may be best suited for a plant-based diet for optimal health and natural living.

1. Our Teeth Tell a Story

Let’s start with our teeth — one of the most telling indicators of our natural diet.

CANINES

While humans do have small canine teeth, this doesn’t mean we’re naturally built for eating meat like true carnivores. In fact, some mostly vegetarian animals — such as gorillas and monkeys — have much larger canines than we do, yet their diets are predominantly plant-based. They may occasionally eat insects or small animals, but their sharp teeth serve more for display, defense, or competition than for eating meat.

Unlike the long, dagger-like canines of lions and wolves — which are designed to tear through flesh and muscle — human canines are short and blunt. They aren’t capable of cutting through meat the way a lion can rip into a deer. Instead, our canines help bite into tougher plant foods, like sugarcane, carrots, or apples — not muscle tissue.

CHEWING – BY MOLARS

Photo by Quang Tri NGUYEN on Unsplash

In contrast, herbivores like cows and deer have broad, flat molars designed for grinding fibrous plant material — and so do humans. Our large molars and premolars are perfectly suited for chewing grains, fruits, and vegetables. Carnivores, however, lack these flat grinding teeth. Instead, they have sharp canines for tearing flesh, not for chewing like herbivores or humans.

Additionally, our jaws are capable of moving side to side — a motion typical of herbivores — which helps us grind food thoroughly. Carnivores, by comparison, have jaws that move only up and down, allowing them to tear and swallow meat quickly without much chewing. Just watch a dog eat — it swallows meat in chunks, barely chewing at all — while humans take time to chew and break food down in the mouth.

Altogether, the structure and function of human teeth and jaws strongly suggest that our bodies are better suited for a plant-based diet than one based on meat.

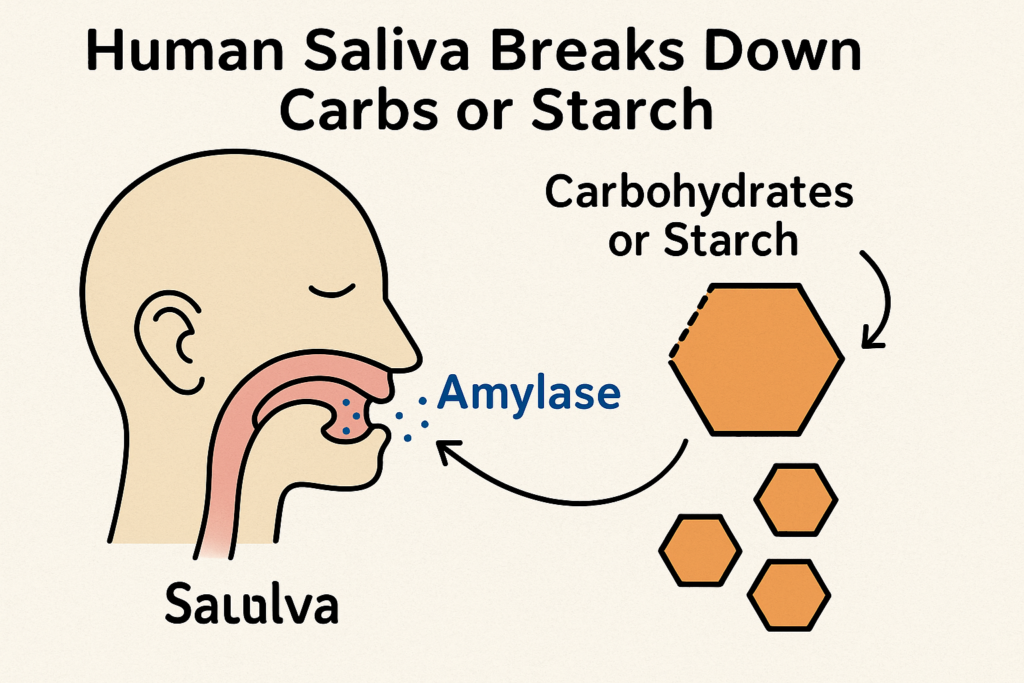

2. Our Saliva Tells a Story Too

Digestion doesn’t begin in the stomach — it starts in the mouth. Human saliva contains an important enzyme called amylase, which is responsible for breaking down complex carbohydrates (like starch) into simpler sugars. This enzyme plays a crucial role in the digestion of plant-based foods, which are rich in starches — such as grains, legumes, potatoes, and fruits.

In contrast, true carnivores do not have salivary amylase because their natural diet — mainly meat — contains protein and fat, but very little to no starch. Since they don’t eat plant foods, there’s no biological need for this enzyme.

The presence of amylase in human saliva is strong evolutionary evidence that our bodies are adapted to digest starchy plant foods, not raw meat. It reflects our biological reliance on carbohydrate-rich plants as a primary energy source.

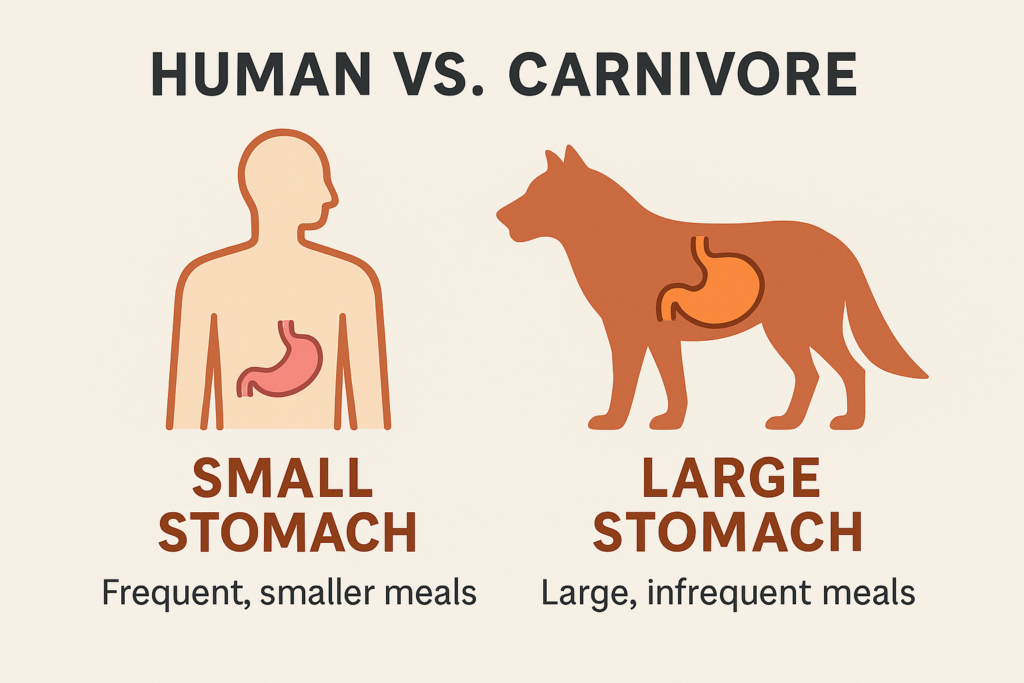

3. What our stomach says (humans naturally plant-based eaters)

Our stomach acid is much weaker than that of true carnivores, who require highly acidic stomachs to break down raw meat and kill dangerous bacteria. For example, a lion’s stomach has a pH close to 1, which helps it digest meat efficiently and safely — even if it’s a few days old. In contrast, the human stomach has a milder acidity (around pH 4–5 when empty), which is ideal for digesting plant-based foods like fruits, vegetables, and legumes, but not raw animal flesh.

This is why carnivorous animals rarely suffer from indigestion or food poisoning — their digestive systems are built to handle raw meat and slow digestion. Humans, on the other hand, are more prone to gastrointestinal issues when consuming meat, especially if it’s undercooked or left out too long. This further supports the idea that our digestive system is naturally suited to a plant-based diet.

Moreover, carnivores often eat large meals at once and can go days without eating again because their stomachs are large and designed for feast-and-fast cycles. For example, wild lions may eat once every few days. Humans, like herbivores, require regular meals and tend to eat multiple times a day. Most herbivorous animals — such as cows, elephants, and gorillas — graze or forage throughout the day to maintain energy levels.

Similarly, the human stomach is relatively small and designed for frequent, smaller meals — a trait shared with herbivorous animals. Unlike carnivores, which can consume large quantities of food in one sitting and go days without eating, humans typically eat multiple times a day — often 2 to 4 meals or more. This regular eating pattern aligns closely with the behavior of plant-eating animals, which graze or forage throughout the day.

When combined with our digestive chemistry, this frequent meal pattern further supports the idea that humans are biologically more similar to herbivores than to carnivores.

4. Intestine: A Plant-Friendly Path (humans naturally plant-based eaters)

Another strong piece of evidence pointing to a plant-based design is our digestive system — particularly the length and structure of our intestines.

Carnivores, like lions and tigers, have very short digestive tracts — typically about 3 to 6 times their body length. This short, straight gut allows meat to pass through the system quickly before it begins to rot or produce harmful toxins. Their digestion is fast and efficient for handling animal flesh, which can putrefy if it stays in the body too long.

Humans, on the other hand, have much longer intestines — around 25 to 30 feet in length, or roughly 10 to 12 times our body length. This is very similar to herbivores such as cows, elephants, and apes, who also have long intestines adapted to slowly break down and absorb nutrients from fibrous plant materials like fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains.

This extended digestion time is especially important for extracting vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, and dietary fiber — all abundant in plant foods. Fiber, in particular, is essential for gut health and regular bowel movements, yet it is completely absent in animal-based foods.

If humans were true carnivores, we would not need such a long gut — in fact, it would likely increase the risk of disease due to meat fermentation and bacterial growth. The structure of our intestines clearly favors plant digestion, not meat.

Our slower, more complex digestion mirrors that of herbivorous animals, reinforcing the idea that we are biologically designed to thrive on a plant-rich diet.

5. Built for Gathering, Not Hunting

Another important clue to our natural diet lies in how our bodies are physically built. Unlike true carnivores, humans lack the biological tools needed for hunting and killing prey without the aid of external weapons or tools.

No Claws or Sharp Teeth

Carnivorous animals, such as lions, tigers, and wolves, are equipped with sharp claws, large canine teeth, and powerful jaws designed to catch, kill, and tear into prey. In contrast, humans have blunt nails, small canines, and jaws that are better suited for grinding than ripping. Our physical bodies are not capable of hunting or killing large animals without tools.

Tool Use Suggests Adaptation, Not Design

Humans began to hunt only after developing tools — sticks, stones, spears, and traps. This shows that meat-eating required adaptation and innovation, not natural ability. A true carnivore doesn’t need to invent weapons — it is born with them. The fact that we needed to create tools to hunt suggests that meat was not our primary or natural food source.

Hands Built for Gathering

Our hands also tell a powerful story. With opposable thumbs, fine motor skills, and a wide range of motion, human hands are perfectly designed for gathering — picking fruits, pulling plants, digging roots, and cracking nuts. These are typical traits of herbivorous animals, not predators.

Vision Designed for Plants, Not Prey

Eye structure provides another fascinating clue. Carnivores generally have eyes positioned at the front of their heads to give them depth perception, which is ideal for tracking and hunting moving prey. They also tend to have more limited color vision, often seeing in shades of blue and green — enough to spot movement, but not color-rich details.

Humans, on the other hand, like most herbivores and frugivores (fruit-eating animals), have eyes positioned on the front but with a wider field of vision. More importantly, we have trichromatic color vision, which allows us to perceive a wide range of colors, especially red, green, and blue. This advanced color vision is not necessary for hunting but is extremely useful for identifying ripe fruits, fresh leaves, and edible plants in nature.

This type of vision is also seen in other plant-eaters, such as certain primates, who rely on color to find nutrient-rich food in dense forests. Carnivores don’t need this — they hunt based on motion, not color.

Conclusion of This Section

From our lack of natural hunting tools to our advanced color vision and gathering-friendly hands, everything about the human body points to an evolutionary design centered around foraging and plant consumption — not chasing down and eating animals.

6. What Do Our Taste Buds Prefer?

Let’s take a moment to think about taste — one of the clearest signs of what a species is naturally drawn to eat.

Are We Attracted to Raw Meat?

Photo by Sergey Kotenev on Unsplash

Be honest — does the idea of biting into a freshly killed, raw animal make you feel hungry or nauseous? Most people would feel disgusted. The sight, smell, and texture of raw flesh or blood usually triggers revulsion in humans. This reaction is instinctual, not cultural. Even young children, who haven’t been taught about diets, often reject the smell or look of raw meat.

In contrast, true carnivores like lions, tigers, or wolves are highly attracted to the smell of blood. It excites their appetite. They consume freshly killed prey without seasoning, cooking, or preparation. They relish it raw, warm, and bloody — something that would make most humans gag.

Our Taste Preferences Are Naturally Plant-Based

Humans, by nature, are drawn to the sweetness of fruits, the crunch of vegetables, and the comfort of cooked, savory plant-based meals. Our taste buds are especially sensitive to sweetness, which is a trait shared with fruit-eating (frugivorous) animals like chimpanzees and orangutans. Sweetness signals energy-rich foods like ripe fruit, which are nutrient-dense and easily digestible.

We also have a strong response to umami (a savory flavor found in mushrooms, tomatoes, and fermented foods) and saltiness — both of which are abundant in plant-based meals when prepared well. But we do not have a natural craving for blood, raw flesh, or the smell of decay — unlike scavengers or predators.

Carnivores vs. Humans: Taste Bud Differences

- Carnivores have fewer taste buds — around 400 to 500 — and their sense of taste is less developed because they rely more on smell for hunting.

- Humans have over 9,000 taste buds, giving us a complex appreciation for flavors, textures, and aromas. This diversity of taste allows us to enjoy a wide variety of plant foods in their natural state.

| Species | Diet Type | Approx. Number of Taste Buds | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Humans | Omnivore / Frugivore | ~9,000 – 10,000 | Strong preference for sweet, umami, and varied plant flavors |

| Cows | Herbivore | ~25,000 | Highly developed for detecting bitter/toxic plant compounds |

| Pigs | Omnivore | ~15,000 | Sensitive to a wide range of flavors; love starches and umami |

| Rabbits | Herbivore | ~17,000 | Prefer bitter and sweet plant compounds |

| Dogs | Carnivore/Omnivore | ~1,700 | Favor meat; less sensitive to sweetness |

| Cats | Obligate Carnivore | ~470 | Cannot taste sweetness; tuned for amino acids (umami) |

| Lions | Carnivore | <500 | Limited taste buds, mainly for protein/amino acids |

| Chimpanzees | Frugivore | ~9,000 – 10,000 (similar to humans) | Crave sweet fruits and have complex flavor preferences |

| Horses | Herbivore | ~25,000 | Sensitive to sweet and bitter, dislike toxins |

This explains why we prefer our meals cooked, seasoned, and combined with herbs, spices, and oils — all of which are plant-derived. Meat, on its own, is bland or unpleasant to most palates unless heavily processed or cooked.

Conclusion of This Section

Our natural cravings and aversions strongly suggest that we are biologically drawn to plant-based foods. From our love of sweet fruits to our dislike of raw flesh, our taste preferences align far more with herbivores and frugivores than with carnivores.

7. Science and Evolution Back It Up

Some people argue that early humans ate meat — and that’s true, to an extent. But the majority of their diet was plant-based: fruits, tubers, nuts, seeds, and leafy greens. Meat was eaten occasionally, mostly when available. Even today, many indigenous populations and cultures thrive on diets rich in plant foods.

Recent studies show that the healthiest diets — those that reduce the risk of heart disease, diabetes, and obesity — are mostly or entirely plant-based. Our biology supports this: we thrive, not just survive, on plants.

8. The Health Benefits of Eating Vegetarian

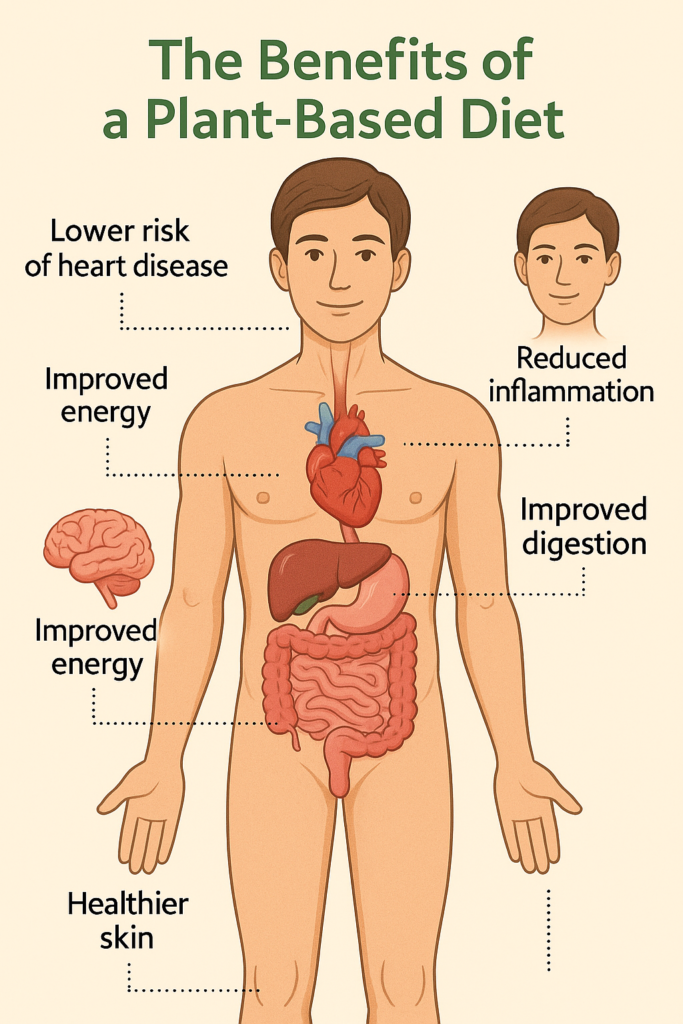

Let’s not forget the health benefits. A plant-based diet has been linked to:

- Lower risk of heart disease and high blood pressure

- Better digestion and gut health due to fiber

- Reduced inflammation in the body

- Improved energy and mental clarity

- Healthier skin and weight management

In short, plant foods nourish us deeply. While our bodies can handle meat, they seem to do best when meals are built around plants.

9. But Aren’t Humans Omnivores?

Technically, yes — humans are omnivores. We can eat both plants and animals. But being capable of something doesn’t always mean it’s optimal. We can also eat junk food, but that doesn’t mean it’s good for us.

What matters is not just what we can digest, but what helps us thrive. And time and time again, research shows that plant-based eating supports long-term health and vitality.

10. Archaeological and Evolutionary Evidence: Our Plant-Based Past

1. Taforalt Cave, Morocco (North Africa)

One of the oldest cemeteries in Africa, the Taforalt site contains human remains dating back over 15,000 years — before agriculture began. Isotopic and dental analysis of the skeletons showed that these early humans consumed a largely plant-based diet, consisting of wild legumes, nuts, seeds, and possibly grains. Their flat molars and heavy tooth wear suggest a lifetime of chewing fibrous, coarse plant material — not meat.

2. The Hadza People of Tanzania

The Hadza are one of the last remaining hunter-gatherer societies. Studies of their diet reveal that up to 70–80% of their daily calories come from plant foods — including tubers, berries, and baobab fruit. While they do hunt occasionally, their primary sustenance comes from gathered plant foods, showing that even hunter-gatherers prioritize plants when available.

3. The Frugivorous Traits of Early Hominins

Early human ancestors, like Australopithecus and Paranthropus, had dental and jaw features consistent with fruit and plant consumption. Their large molars, thick enamel, and powerful chewing muscles suggest they were well-adapted to a high-fiber, low-meat diet. Fossilized remains of food particles found on ancient teeth also show plant starches — not animal protein — as a major part of their diet.

4. Isotopic Evidence from Europe and Asia

Isotopic analysis of Neolithic and Mesolithic human bones in Europe and Asia has repeatedly shown that plant-based diets were dominant before and during the agricultural transition. Even early farmers consumed diets rich in grains, legumes, and vegetables, with meat playing a minimal role.

5. Tools for Processing Plants, Not Hunting

Archaeological digs often uncover ancient grinding stones, pestles, and mortars used to process grains, nuts, and seeds. These tools appear far more frequently than hunting weapons in many early human sites — another clue that plant foods were central to survival and daily life.

Conclusion of This Section

From African caves to modern tribal communities, the archaeological record consistently points to a diet rooted in plants. Early humans didn’t chase down prey for every meal — they gathered fruits, dug up tubers, cracked nuts, and processed wild grains. The tools they used, the wear on their teeth, and the chemical signatures in their bones all reinforce one clear idea: our ancestors were gatherers, and our bodies evolved with plant foods as the foundation of our diet.

Conclusion: So, Are We Designed to Be Vegetarian?

From our teeth to our digestive tract, from our instincts to our health outcomes — the evidence strongly suggests that the human body is better suited for a vegetarian (or primarily plant-based) diet. While we may be able to eat meat, our bodies seem to function at their best when powered by plants.

So, whether you’re considering a shift for health, ethics, or the environment, know this: your body may just be cheering you on.

Do Plant-Based Diets Lack Nutrients? Science Says No.

A common myth is that vegetarian or vegan diets lack essential nutrients and are not suitable for all age groups. However, research from major health organizations and scientific studies strongly disagrees.

The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics — the largest organization of food and nutrition professionals in the U.S. — clearly states:

“Appropriately planned vegetarian, including vegan, diets are healthful, nutritionally adequate, and may provide health benefits in the prevention and treatment of certain diseases. These diets are appropriate for all stages of the life cycle, including pregnancy, lactation, infancy, childhood, adolescence, older adulthood, and for athletes.”

This means a purely plant-based diet — even without dairy or eggs — can provide all essential nutrients, including protein, iron, calcium, omega-3s, and vitamins like B12 and D, when planned properly.

When planned thoughtfully, a 100% plant-based (vegan) diet is safe, complete, and healthy for people of all ages — including children, pregnant women, and older adults. The claim that a vegetarian diet is nutritionally inadequate is outdated and not supported by modern science.

: – humans naturally plant-based eaters -:

References

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. (2016). Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Vegetarian Diets.

➤ https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2016.09.025 - Humphrey, L. T. et al. (2014). Earliest evidence for caries and exploitation of starchy plant foods in Pleistocene hunter-gatherers from Morocco. PNAS, 111(3), 954–959.

➤ https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1318176111

Amazing knowledge really mind blowing।Really our suits most plant based foods।